Dispatches from the Front Lines #1

Dispatches from the Front Lines is intended to document a very few of the many acts and actions that are taken by ordinary people to push back against Australia’s system of indefinite mandatory detention, without charge or trail, of asylum seekers. Some of these accounts will be of very personal acts of compassion and kindness. Some will be of deliberate and explicit defiance of laws that breach basic human rights. All will attempt to show by example how we can collectively push back against the racism, cruelty, injustice, erosion of human rights and basic democratic principles that are inherent to the treatment of asylum seekers by successive Australian governments over more than 20 years.

A Woomera Story – Part One

This is an account of the participation by six friends in the protest by some 1500 ordinary Australians that occurred at the Woomera detention centre over the Easter long weekend in 2002. The names of people participating have been changed. The home towns of people described have be obfuscated.

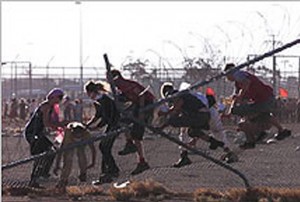

What was most distressing was seeing the refugee children behind the razor wire. All that separated the protesters and the refugees inside the detention centre was a four meter high steel-picket fence and a roll of razor wire at its base. If you put one arm between the pickets and used your other hand to pull yourself hard into the fence, stretching through as hard as you could, you could reach about half way over the roll of razor wire that was just inside the outer fence. If an asylum seeker standing between the inner and outer fences leaned carefully over this roll of razor-wire you could barely shake hands.

I shook many hands in this way. ‘Azadi’, I said, using the Farsi word for ‘Freedom’ as I shook one hand after another, including that of a little boy who can’t have been more than 12 years old. The refugees were chanting and expressing themselves. There were many protestations of gratitude ‘Thank you for coming’. There were statements of protest ‘ACM, Mafia’ was one that I remember, referring to the detention contractor, Australasian Correctional Management.

Our little band of six activists and sympathisers had driven about 30 hours to get to the ‘Woomera 2002: Festival of Freedoms’. The detention centre was located just outside the Woomera township, in the Woomera prohibited area, South Australia. Located some 500 km north of Adelaide the township has a long military history, having been used as a base of operations for testing on the Woomera rocket range.

Choosing such an isolated place for an immigration detention centre was no accident. It allowed the government maximum ability to restrict access to information about what went on there. This in itself was a reason to go. I quickly coined the phrase, ‘No distance is too far to travel in order to challenge the human rights abuses being perpetrated by this government’.

What had brought us here was our utter disgust at the toxic racist politics that was prevailing in Australia in the lead up to Easter in 2002. We’d had the MV Tampa affair where Prime Minister John Howard had sent in the SAS to prevent Captain Arnie Rinan from landing refugees he’d rescued at sea. We’d seen blatant and deliberate lies by the immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock about children being thrown overboard.

We’d seen hunger strikes and people self harming. Refugees had dug their own graves and lay in them under the searing summer sun of the Woomera desert in order to protest against the arbitrary suspension of processing of their refugee claims. Only several months earlier a man had leapt, belly flop style, several meters onto razor wire in protest at what was happening to refugees in Australia’s immigration detention system. This courageous resistance by the refugees themselves compelled us to take action in solidarity with them.

Consequently, when the word started to percolate through the refugee activist community about going to Woomera at Easter in 2002, a couple of us active locally quickly decided ‘We have to go’. There were many of us who just wanted to say in some way ‘No, we reject these politics. We repudiate the racism and hatred being incited and exploited by the government.’

Woomera 2002: Festival of Freedoms

We left for Woomera on the Wednesday evening before Good-Friday, driving an eight seat people mover I’d bought just for this trip. It was about a 30 hour drive, but with six of us to share the driving it wasn’t too bad.

The group was eclectic. A university administrator, a research scientist, a musician, a student politician, a postgraduate student and a mother of two. Paul seemed to like playing the role of curmudgeon and would comment on passing through each small country town “I hate country towns, fucking stinking holes”. At one point we had a cursing competition. Tanya’s winning contribution was “Fuck! The fucking fucker’s fucked!”. The journey there was a good bonding opportunity.

We arrived at the Pimba road house, also known as Spuds Road House, on the Stuart Highway in the early afternoon of Good-Friday. The road house was the publicised ‘muster point’ for people attending the convergence and was at the turn-off for Woomera. There we met the ‘briefing team’, who explained the present state of affairs and issued us with a copy of the ‘Woomera convergence handbook’.

During our briefing we learned that the night before a small advance team had staked out a good camping site only a kilometre from the detention centre. The Federal Police had taken exception to this had tried to evict the team from the site. After a failed attempt at making an arrest the AFP had backed down and the camp site was held. This later to proved to be a critical tactical victory. One of the alternative camp sites that the AFP had designated was at Spuds road house. That’s seven or eight kilometres from the detention centre and would have made an effective protest impossible.

The rest of our briefing was about conditions and circumstances which included the request that we park our vehicle and trailer so as to contribute to a protective ring around the protest camp. This was an attempt to fortify the camp again against police incursions or further attempts to break it up. With this information and advice we headed the last six or seven kilometres up the road to the convergence camp site.

Getting there in the early afternoon we would have been among the last to arrive. The camp would already have been about 1500 strong, which is far more than we or anybody else ever expected. As we’d been advised to do people were parking their vehicles so as to try and make a secure perimeter. Within this perimeter the camp was fairly tightly cluttered with tents. There was a water tanker, portable toilets, a communications tent, legal observers and a first aid tent. The atmosphere was already excited and optimistic when we arrived.

All of this had been achieved by organising online using a decentralised and non-hierarchical model. Using the convergence web site, various groups and individuals had just declared their interest in providing this or that service, or undertaking this or that task, tactic or action. Like minded and like intentioned individuals and groups thus aggregated and formed ‘affinity groups’. In this way all the necessary coordination, infrastructure, services and actions were organised.

Our group of six thought that we were well prepared. We had driven further than almost anyone else to be there. We had a wide variety of equipment to cope with all sorts of contingencies and scenarios. This included hand held radios, maps, spare phones, some fireworks. We even had a telescope for long distance observation of the detention centre in event that we were not able to get close. This seemed very likely. We were keen and we ready, or so we thought.

In the event, it only took from 2 pm on Good-Friday when we arrived, until 6 pm to disabuse us of our perception of preparedness. Only 4 hours to be confronted with our own utterly inappropriate state of mind and mental focus. We were totally caught off-guard by what happened, late in the afternoon that Good-Friday at Woomera Detention Centre in 2002.

A Call to Action

It was not long after our arrival at the convergence camp site before the decision making forum for the convergence, the ‘spokes council’, was convened. We heard that the word from refugees in the detention centre, a mere one kilometre away, was that they welcomed us and wanted to meet us face to face through the fences. There was no dissent to the suggestion that we march on the detention centre.

Without any order or command we moved off north along the main road that lead to the front gate of the centre. The procession of protesters wend it’s way to a temporary fence which blocked the road north. At this point the fence was well backed up with police officers, Australian Federal Police and South Australian Police. It extended in a line running east to west at least a hundred meters either side of the main road.

Rather than stopping in the face of this obstacle on the road, the lead elements just turned left and headed west into the desert. This turned out to be another critical decision, though I have no idea if it was a deliberate or conscious one. Somehow though I think that it was such on the part of some people who were thinking tactically.

The long winding throng of protesters sported a multitude of banners and flags. You could see the black flags borne by anarchists, the red banners of the various flavours of socialists, green carried by The Greens. There were religious groups, NGOs, community groups, human rights groups and environmental groups. There were some who were just there as individuals or small groups of friends, not identifying with any particular group or political tendency.

When we reached the western extent of the temporary fence we turned north again, in the general direction of the detention centre. After a kilometre or so we came up against a permanent chain link fence. When the foremost elements of the procession were arriving at this fence I was about one third of the way back, some 100 meters or so. Yes the procession was probably about 300 meters long.

Through the dust that was being kicked up from the cavalcade I could see that people had already started to scale this fence. I was not sure where the rest of my companions were, we had become separated in the completely unmanaged excursion across the Woomera desert. I raised Greg on my hand held radio, “They are on the fence” I said hurrying forward to where the action was, “come on!”. We’d only been here a few hours and this was already getting exciting!

When I got to the fence, I realised that this was not a part of the detention centre. This fence, a normal chain link fence topped with a roll of razor wire, was part of an interconnected series of compounds which appeared to be disused. On the far side of these compounds was an east-west running road. The detention centre was on the far side of that road.

Quickly I joined others who were climbing the fence. We could not get over the razor wire at the top, so we just shook the fence as much as we could. I could see the refugees in the detention centre still 200 meters away. They were on roofs and fences themselves, waiving arms and holding up banners that they had made. I wanted to communicate with them, to let them know that I was here objecting to their detention, ‘Azadi, Azadi’ I boomed.

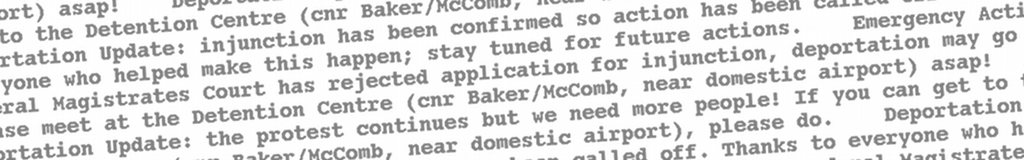

I was rocking on the fence furiously while many more people were doing the same from the ground, when it just came down. So many people had put their weight on it that it just fell outwards. I had a moment of alarm when I realised that it was coming down on me. I found myself hanging by my hands on a fence that was well on it’s way to laying flat on the ground. However, I did land on my feet rather gently and manage to scramble out of the way.

Not content with a small section of the fence being down, people who had managed to cross over the roll razor wire, which was now at ground level, began running up on the section of fence that was only partially down. That is the part between the section laying flat on the ground and the sections still standing upright. I joined them to add my weight to the effort and even more fence obligingly came down. In just a few short minutes we had brought down more than 50 meters of this fence line.

With such a large breach many people were emboldened to cross. However, a surprising number did not. It’s amazing how much authority a line can have. There was of course the suspicion that this must be some sort of a trap. It was in my mind and in the mind of many others that at any moment a platoon of officers might appear behind us and have us trapped.

These fears were not realised and no police came. Several hundred people just went for it, crossed the fence, passed through the series of interconnected compounds and made it right up to the detention centre proper.

Without any planning it happened that we came up to the detention centre fence at the high security ‘Oscar’ compound. This was the compound for ‘trouble makers’. That is, people who have the temerity to object and protest at being held in desert prison camps, indefinitely, without charge or trial.

Oscar compound had a double steel picket fence that was some three or four meters high. Ceaser’s double circumvallation at the siege of Alesia sprang to mind, though I was not sure if the historical comparison was valid, nor who was analogous to Vercingetorix’s Gauls and Caesar’s Romans.

There was perhaps a four meter space between the fences. Both the inner and the outer fence were topped with the ubiquitous coils of razor wire, with the outer fence having an additional roll of razor-wire at its base in the gap between the two fences.

We were all pressing up against this fence. Somehow, refugees had got between the two fences. In spite of the language barrier there was communication going on, with refugees thanking protesters for coming, showing the self-harm scars on their bodies, and asking for help. Some of them were sporting cuts from having tangled with razor-wire.

There were still very few police about at this point. I remember seeing one AFP officer standing rather incongruously at his station, looking rather lonely all dressed up in his riot gear, helmeted, carrying his shield. There was another historical analogy, Roman legionary.

He looked rather like he did not know what to do. There were after all a couple of hundred protesters violating the no-go zone and there really was nothing at all he could have done about it even if he had dared try. So he just stood there standing all stern almost as if at attention, pretending not to see us. We returned the courtesy and ignored him.

Some protesters were making feeble efforts at the fence, kicking it and tugging at it. But they had no chance. It was a rather more robust obstacle than the chain-link fence that we’d just taken down. This was another reflection of the fact that nobody had ever dreamed that we’d get up to the detention centre. If I’d have thought that there was any chance of this happening I’d have brought something that would have had some hope of breaching this fence. My companions and I seemed to have brought something to cope with every other contingency that we could imagine. For this however, we had nothing. So I started looking about for something that could be used.

There was an assortment of ACM 4WD vehicles parked nearby. I briefly thought of breaking into one so that we could use it as a battering ram. They were rather conveniently parked perpendicular to the detention centre fence. All we needed was to get the hand brake off and get the vehicle in neutral. They were already pointed at the fence so we did not need to defeat the steering lock or start the engine. It could have worked. Tens of people pushing a one ton or more vehicle could be a pretty effective battering ram. When it came to it though, I baulked.

I had not come to Woomera with the correct frame of mind and such a blatant act of defiance and challenge to the system was not something that seemed realistic to me in that moment. Later I realised that the people who had baulked at crossing the downed fence had exactly the same reaction I was having at the thought of using one of these vehicles as a battering ram. They were just having the reaction at a lower threshold.

After some time a platoon of police officers in varying degrees of riot equipment arrived and tried to persuade us to back off from the fence. The sergeant in charge of the platoon was really trying so hard to negotiate us backing away, but he was pretty much ignored. It was as this point that some of the people in detention produced a piece of galvanised steel pole of the sort that the chain-link fences are made from. Clearly they were better organised and more resourceful that we were.

Paul was quite close to the spot where the refugees had taken to the fence, using the pole as a makeshift pry bar. You could see that one of the pickets was yielding a bit. Then there was a sharp ‘PANG’ as the fastening rivets gave way. Suddenly there was a picket missing in the outer fence. Paul thought ‘Wow, they got a picket off’. Momentarily he realised that people were squeezing through the gap. People were escaping!

This was something that I and many others were totally unprepared for psychologically and tactically. I was still stuck in a mind set of ‘we will never get near the fence’ and ‘the police will be in total control’. As a consequence I did not act very quickly or thoughtfully. I operated with poor assumptions and failed to exploit opportunities when they arose.

This was something that I and many others were totally unprepared for psychologically and tactically. I was still stuck in a mind set of ‘we will never get near the fence’ and ‘the police will be in total control’. As a consequence I did not act very quickly or thoughtfully. I operated with poor assumptions and failed to exploit opportunities when they arose.

Some people however knew what the correct thing to do was. They linked arms and tried to obstruct the police in their efforts to arrest refugees as they were slipping through the fence. Soon the police had forced themselves between the protesters and the fence. However, this did not stop the escapes. Now the refugees were simply leaping over the police officer’s heads into the arms of the protesters and crowd surfing to freedom.

At one point I rather lamely helped someone pretend to be an escaping refugee, playing the role of the protester trying to hide an escaped refugee and assist him in getting away from the detention centre. This was a completely pointless and absurd effort to confuse the police. Things were already very confused. The police had already lost control of the situation.

These actions were a reflection of not being psychologically prepared. You see all sorts of absurd ideas coming up in exciting or fear producing situations unless there is careful forethought about how you will respond under what circumstances. The correct thing to do would have been just to help more people escape and physically obstruct police trying to arrest escapers. I failed to appreciate that it was the refugees and the protesters who had the initiative and upper hand.

I also fell back from the fence far too early. Once the first few people had escaped I was thinking ‘that’s it, any moment there’s going to be a strong police response. It’s time to get out of here with the few who’ve escaped before they have no chance’. Wrong again.

The efforts to physically obstruct police and help people escape continued for as much as fifteen minutes or more after I left and headed back to camp. There were at least some protesters who had the correct instinct to resist and challenge. It would have been better if more had been willing to cross the downed fence and more had the presence of mind to link arms and hold their ground when the police moved in to try and arrest escaping refugees.

There were however some acts of initiative and quick thinking among the protesters. On the way back to the camp I spotted Paul from our little travelling company. He was, rather absurdly and a little disturbingly, walking though the desert in nothing but his green jocks and a pair of boots. He’d seen one of the escaped refugees dressed in ACM issued clothing. This was very bright and very distinctive. In a moment of solidarity and inspiration he’d given the refugee all his clothes which included a brand new pair of jeans. This was excellent for the refugee who now was able to blend into the crowd much more effectively.

It did of course leave all of us to deal with the spectacle of Paul in his green jocks, with expanses of pale skin and a bit of a beer gut. It is a memory that I willingly endure because it was all in the interests of fighting an unjust and cruel system.

Once back at camp there were escaped refugees who were trying to hide there. With most of the protesters still not back from the fence, police were coming into the camp and picking them off. I have to admit that I just watched this happen. I could have distracted and obstructed the few police who were in the camp doing this. Another example of a bad mind set and being too slow to shift out of it.

By the time it got dark I’d had an hour to really evaluate my decisions and actions. I quickly realised how poorly I’d done and why. Bad mind set, assumption of police control, scared to challenge police authority. What was the point of the campaign if it was not to challenge the power to detain people indefinitely without charge or trail? I was disappointed in myself, but I’d soon have an opportunity to make up for it.

Accepting Responsibility

Soon after sunset, one of our travelling companions, Beth, noticed two men hanging about our spot within the convergence camp. On talking with them she learned that their names were Ali and Farhod. They’d escaped from the detention centre that afternoon and had managed to avoid being arrested before dark.

Ali was an Hazara from Afghanistan. He was barely 20, if that, and had been in detention for over 18 months. Farhod was Iranian and in his early 30s. He’d been in detention for less than 12 months.

It was clear that Ali’s detention experience had been a difficult and painful one. He had scars all up and down his arms from self harming and was one of those who had previously drunk shampoo hoping that it would kill him. He’d also participated in the very serious and dangerous mass hunger strike earlier that year that had forced Immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock to restart the processing of the asylum claims of Afghanis. His time in detention had left him physically and psychologically depleted. Farhod on the other hand was psychologically relatively intact, physically OK and had better English.

Naturally our minds turned to the question of what we could do to help these two men. Everyone was thinking that at some point the police were going to raid the camp looking for escaped refugees. They’d already put up road blocks and thrown a cordon around the camp. Some activists that we knew had already been arrested trying to drive escaped refugees out of the area. Certainly we had to go home at some point, so these guys had to leave also. All over the camp there were protesters facing the same problem. What to do? How to help the refugee or two who’d somehow come into their care.

As our little group was having a conversation about all this I became aware that I was faced with a serious dilemma. There were some really poor ideas being bandied about, mainly as a result of this all being well outside of anyone’s experience. However, it was very clear to me what the solution was. I knew I had the equipment, skills, experience and knowledge to implement the solution I had in mind. I knew there were risks in it for me and I was afraid of them. I wanted to stay quiet and say nothing. At the same time I did not want to be a hypocrite in my opposition to mandatory detention or be someone who failed to act when they had a chance to do so. When I boiled it all down the potential negative consequences to me paled into insignificance when compared to the suffering that Farhod and Ali had already endured and would probably continue to endure if I did not help them.

So I spoke up, “Someone has got to walk these guys out of here, through the police lines. They won’t make it otherwise.” Paul was incredulous “Who can do that?”, as though this was the stuff of Hollywood movies or adventure novels. Then came the difficult moment. I still had the option of just staying quiet. Instead I spoke four little words that framed the course of the entire weekend for me, and for the two men for whom we had now accepted the responsibility for helping. “I can do it”. Once I’d said it there was no backing out. My travelling companions had implicitly agreed to participate in this endeavor.

Now we just had to live up to that commitment.

Read Part Two for the conclusion to this story.

RRAN Meetings

RRAN WA and Fremantle RRAN meet the first Monday of the month at 6.30pm at the Boorloo Activist Centre, U15/5 Aberdeen Street, Perth (just north of the McIver Train Station or online via Jitsi. For more details, send us a message via our Contact RRAN WA page, or call/text us on 0412 860 168. Contact Fremantle RRAN