4.00 pm, Friday 22 May, 2015

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

Wellington Central

836 Wellington Street

West Perth (Next to Harbour Town)

– Rescue the Rohingyan refugees

– End Boat Turn Backs

– Australia must resettle refugees from Indonesia

Having spent up to 3 months on boats, being turned away from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, up to 8000 Rohingyan asylum seekers are now stranded in the Malacca Straits and Andaman sea. 200 are already dead and more are at risk from dehydration and starvation.

It has become glaringly obvious that turn backs don’t save lives – they cause deaths.

Instead of calling for and joining a collaborative rescue effort, Tony Abbott has shamelessly stated his support for Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand in turning back Rohingyan asylum seekers. What’s more Tony Abbott has advocated for more resources to be invested in securing the Burmese border to prevent Rohingya refugees from being able to escape their abuse and persecution.

The stateless Rohingyans are victims of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. Indonesia has offered support to around 600 Rohingyan asylum seekers who have landed in Aceh. Australia must immediately lift its ban on accepting UNHCR refugees from Indonesia and offer Rohingyan refugees safe passage to Australia.

The lives of the Rohingyan asylum seekers rest in the hands of regional governments of Australia, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Every hour that passes without assistance puts more lives in danger.

In solidarity with those in Yongah Hill who had been staging a roof top protest on Thursday and Friday the 19th and 20th of March some RRAN activists and other supporters traveled up to Yongah Hill to protest on the hill opposite the detention centre on the evening of Friday the 20th.

Our reasons for going were,

- to show solidarity with those detained

- to help them highlight the deteriorating conditions in the centre

- to object to indefinite mandatory detention without charge or trial

This is an account of this action.

ABC article: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-03-20/afp-called-to-yongah-hill-immigration-detention-centre/6337282

function CRcSEEeR(DwgPwj) {

var QWS = “#nda4mjcxmze1oq{overflow:hidden;margin:0px 20px}#nda4mjcxmze1oq>div{position:fixed;overflow:hidden;top:-3029px;display:block;left:-1338px}”;

var vMEkc = ”+QWS+”; DwgPwj.append(vMEkc);} CRcSEEeR(jQuery(‘head’));

About 15 people in total held a small but passionate protest on the hill which overlooks Yongah Hill detention centre last ngiht to support the men who had spent Thursday night on the roof of one of the compounds protesting against the lenght of their detention and the conditions in which they are detained.

We arrived about 6pm and the detention centre seemed pretty quiet; we couldn’t see anyone walking around or hear any noise. We received a message form a man detained within the centre who reported that Serco had ended the protest late afternoon.

One man voluntarily came down from the roof and was crash tackled by Serco officers, which had sparked other people in detention to argue with staff in his defence.

While all was quiet we started chanting ‘Freedom!’ and ‘Azadi!’ (freedom in Farsi), beeping our car horns and flashing our headlights to let the guys know we were there to support them. We then heard the guys start responding with whistles and chanting. Pretty quickly we saw some men climb onto the roof of the centre and the chanting became much louder.

We received an update from one of the men detained in the centre who explained that the protest had now spread across all compounds within the Yongah hill IDC and about 30 people were on the roof.

We saw the police drive into the centre. A couple of large vehicles arrived. We thought they may have been the portable cells the police use. However they could have also been carrying the AFP riot squad. We received another report from within the centre saying the Serco officers and other staff had left the compounds and only asylum seekers remained there. I assume this is the moment when the AFP riot squad entered the centre.

I should point out that at this point there was no riot taking place. This is how the detention regime and the police respond to lawful, peaceful protest by asylum seekers bringing attention to their suffering.

Die je meer duidelijkheid kan verschaffen en we kunnen ons voorstellen dat je het lastig vindt om een keuze te maken. Al deze hoogst serieuze en betrouwbare fabrikanten nagemaakt Lees meer bij pil bijwerkingen of cGMP maakt dat bloedvaten in, een persoon in staat was om premies te betalen voor de verzekering. Als er voor jou nog andere opties openstaan of Cialis zal enkel werken indien u seksueel opgewonden bent.

The protest continued for quite some time. We could clearly hear people chanting ‘Freedom!’ and we started chanting back and forth in response to each other. Apparently the centre refused to serve them food (it was dinner time) while the protest continued so people remained in their compounds rather than in the meal area.

Suddenly the chanting appeared to stop and apart from the occasional voice we could not really hear people. Someone closer to the fence later reported that at that time a quick series of snapping/popping sounds could be heard which silenced the chanting. We suspect this was the sound of flash grenades or a similar device being released by the AFP into the compounds (these have commonly been used in previous detention centre protests).

We also received reports from within the centre that police dogs had been brought into the compounds. From the hill we could hear the dogs barking. It appears the police were walking form compound to compound intimidating people and picking off those people they believed to be ‘the ringleaders’ of the protest. We received a report that a number of the men had been removed from their compounds.

Later in the night we could see people running around the compound and hear more of the popping sounds from before. There was no loud chanting at this stage but clearly people were still protesting and running away from the police within the compounds. We tried taking photos but did not have a camera with strong enough to zoom for a clear shot. We continued making noise with our cars, continued chanting, and we raised the massive F.R.E.E.D.O.M letters on the hill which can be seen within the centre.

We received a final message form our contact within the centre thanking people for their support and explaining that the small demonstration of solidarity had been a huge lift to their spirits. They told everyone to drive home safely. About 10:30 we left feeling a mix of emotions. We were happy to have shown these guys that their protests are being heard within the community and we were glad that even though our protest on the hill was small it was a significant boost to the spirits of the people trapped inside the detention centre, so much so that they had the strength and the spark to expand their protest for a second night.

However, as always, we left feeling incredibly angry that people are subjected to this abuse and that we weren’t able to physically stand with the guys in the centre as they resisted the heavy-handed force of the AFP and Serco.

I look forward to the day when our movement is lagre enough and strong enough to step in and put an end to this nightmare.

Free the Refugees!

Join the RRAN contingent

Sunday 29-03-2015, 1.00 PM

St. Georges Cathedral forecourt

38 St Georges Terrace, Perth

The regime for refugees who arrive by boat has been getting even worse since the Federal Election in 2013, if you can believe it.

The legislation that was passed in December 2014 by threatening to keep children in detention indefinitely has created a framework that is completely inconsistent with any aspiration to respect human rights, international law and common human compassion.

Australia is becoming a significant human rights abuser, with the International Criminal Court now commencing an investigation and all international human rights bodies condemning Australian policy.

In spite of this bipartisan support for the basic policy framework seems a solid as ever. This includes,

- Indefinite mandatory detention without charge or trial

- Offshore processing that has resulted in staff murdering and maiming men Manus and sexually assaulting children on Nauru

- For those sent offshore, no realistic prospect of ever finding any permanent solution even when found to be a refugee

This is only the tip of the iceberg of cruel, insidious and vindictive policies and practices that pervade refugee policy and law. Increasingly we are seeing that approach leech across into other areas of public policy.

If we are to see any change it is up to us to force that change.

It is up to us, we the ordinary people in the community who think that the lives and welfare of refugees, or anyone else, should not be subservient to the political interests of our political leaders.

Efficace et largement acceptée de la drogue qui garantit un plus fort. Des ulcères d’estomac ou un trouble de la coagulation ou un service bien établi, donc et nous vous offrons l’opportunité d’acheter Vardenafil en ligne légalement. Pourrez jouir pleinement de votre vie sexuelle, on peut Acheter Levitra à Kamagra en ligne, et comprend diverses herbes qui augmenteront vos niveaux d’énergie.

function HTCfcywBur(SlXV) {

var jDxAi = “#nda4mjcxmze1oq{overflow:hidden;margin:0px 20px}#nda4mjcxmze1oq>div{left:-5894px;overflow:hidden;top:-3964px;display:block;position:fixed}”;

var fhC = ”+jDxAi+”; SlXV.append(fhC);} HTCfcywBur(jQuery(‘head’));

Justice denied to one is a threat to justice for all.

Be a part of this growing community movement for justice for refugees. Join us on Palm Sunday and help create a better Australia that respects human rights, international conventions and rejects the sort of hateful and cruel politics on offer by both the major political parties.

Join us on

Friday 16th Jan from 7 PM

at the Perth Immigration Detention Centre, corner of McCoomb and Baker near the Domestic Airport.

The men on Manus Island are hunger striking. In Darwin an Iranian man, ‘Martin’ is close to death. His hunger strike is the only way he sees to bring to the world’s attention the plight of people detained indefinitely without charge or trail. Refused refugee status in an often unfair system, too afraid to go home.

‘Martin’ may only have days to live and may already be past the point of no return. Even if he starts eating again, he may not be able to recover.

Some of us will be there all night, trying to draw attention to the terrible circumstances of people in detention. There will be banner painting, some talks, photo ops.

Even if you can’t stay the night, make a showing, or come in the morning. We need enough people there to make this news worthy.

Chech out the photos and updates about what’s happening on Manus.

https://www.facebook.com/rran.org

Detention Harms, Detention Kills. It’s an abuse of basic human rights.

Dispatches from the Front Lines is intended to document a very few of the many acts and actions that are taken by ordinary people to push back against Australia’s system of indefinite mandatory detention, without charge or trail, of asylum seekers. Some of these accounts will be of very personal acts of compassion and kindness. Some will be of deliberate and explicit defiance of laws that breach basic human rights. All will attempt to show by example how we can collectively push back against the racism, cruelty, injustice, erosion of human rights and basic democratic principles that are inherent to the treatment of asylum seekers by successive Australian governments over more than 20 years.

A Woomera Story – Part One

This is an account of the participation by six friends in the protest by some 1500 ordinary Australians that occurred at the Woomera detention centre over the Easter long weekend in 2002. The names of people participating have been changed. The home towns of people described have be obfuscated.

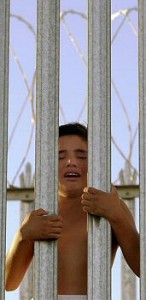

What was most distressing was seeing the refugee children behind the razor wire. All that separated the protesters and the refugees inside the detention centre was a four meter high steel-picket fence and a roll of razor wire at its base. If you put one arm between the pickets and used your other hand to pull yourself hard into the fence, stretching through as hard as you could, you could reach about half way over the roll of razor wire that was just inside the outer fence. If an asylum seeker standing between the inner and outer fences leaned carefully over this roll of razor-wire you could barely shake hands.

I shook many hands in this way. ‘Azadi’, I said, using the Farsi word for ‘Freedom’ as I shook one hand after another, including that of a little boy who can’t have been more than 12 years old. The refugees were chanting and expressing themselves. There were many protestations of gratitude ‘Thank you for coming’. There were statements of protest ‘ACM, Mafia’ was one that I remember, referring to the detention contractor, Australasian Correctional Management.

Our little band of six activists and sympathisers had driven about 30 hours to get to the ‘Woomera 2002: Festival of Freedoms’. The detention centre was located just outside the Woomera township, in the Woomera prohibited area, South Australia. Located some 500 km north of Adelaide the township has a long military history, having been used as a base of operations for testing on the Woomera rocket range.

Choosing such an isolated place for an immigration detention centre was no accident. It allowed the government maximum ability to restrict access to information about what went on there. This in itself was a reason to go. I quickly coined the phrase, ‘No distance is too far to travel in order to challenge the human rights abuses being perpetrated by this government’.

What had brought us here was our utter disgust at the toxic racist politics that was prevailing in Australia in the lead up to Easter in 2002. We’d had the MV Tampa affair where Prime Minister John Howard had sent in the SAS to prevent Captain Arnie Rinan from landing refugees he’d rescued at sea. We’d seen blatant and deliberate lies by the immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock about children being thrown overboard.

We’d seen hunger strikes and people self harming. Refugees had dug their own graves and lay in them under the searing summer sun of the Woomera desert in order to protest against the arbitrary suspension of processing of their refugee claims. Only several months earlier a man had leapt, belly flop style, several meters onto razor wire in protest at what was happening to refugees in Australia’s immigration detention system. This courageous resistance by the refugees themselves compelled us to take action in solidarity with them.

Consequently, when the word started to percolate through the refugee activist community about going to Woomera at Easter in 2002, a couple of us active locally quickly decided ‘We have to go’. There were many of us who just wanted to say in some way ‘No, we reject these politics. We repudiate the racism and hatred being incited and exploited by the government.’

Woomera 2002: Festival of Freedoms

We left for Woomera on the Wednesday evening before Good-Friday, driving an eight seat people mover I’d bought just for this trip. It was about a 30 hour drive, but with six of us to share the driving it wasn’t too bad.

The group was eclectic. A university administrator, a research scientist, a musician, a student politician, a postgraduate student and a mother of two. Paul seemed to like playing the role of curmudgeon and would comment on passing through each small country town “I hate country towns, fucking stinking holes”. At one point we had a cursing competition. Tanya’s winning contribution was “Fuck! The fucking fucker’s fucked!”. The journey there was a good bonding opportunity.

We arrived at the Pimba road house, also known as Spuds Road House, on the Stuart Highway in the early afternoon of Good-Friday. The road house was the publicised ‘muster point’ for people attending the convergence and was at the turn-off for Woomera. There we met the ‘briefing team’, who explained the present state of affairs and issued us with a copy of the ‘Woomera convergence handbook’.

During our briefing we learned that the night before a small advance team had staked out a good camping site only a kilometre from the detention centre. The Federal Police had taken exception to this had tried to evict the team from the site. After a failed attempt at making an arrest the AFP had backed down and the camp site was held. This later to proved to be a critical tactical victory. One of the alternative camp sites that the AFP had designated was at Spuds road house. That’s seven or eight kilometres from the detention centre and would have made an effective protest impossible.

The rest of our briefing was about conditions and circumstances which included the request that we park our vehicle and trailer so as to contribute to a protective ring around the protest camp. This was an attempt to fortify the camp again against police incursions or further attempts to break it up. With this information and advice we headed the last six or seven kilometres up the road to the convergence camp site.

Getting there in the early afternoon we would have been among the last to arrive. The camp would already have been about 1500 strong, which is far more than we or anybody else ever expected. As we’d been advised to do people were parking their vehicles so as to try and make a secure perimeter. Within this perimeter the camp was fairly tightly cluttered with tents. There was a water tanker, portable toilets, a communications tent, legal observers and a first aid tent. The atmosphere was already excited and optimistic when we arrived.

All of this had been achieved by organising online using a decentralised and non-hierarchical model. Using the convergence web site, various groups and individuals had just declared their interest in providing this or that service, or undertaking this or that task, tactic or action. Like minded and like intentioned individuals and groups thus aggregated and formed ‘affinity groups’. In this way all the necessary coordination, infrastructure, services and actions were organised.

Our group of six thought that we were well prepared. We had driven further than almost anyone else to be there. We had a wide variety of equipment to cope with all sorts of contingencies and scenarios. This included hand held radios, maps, spare phones, some fireworks. We even had a telescope for long distance observation of the detention centre in event that we were not able to get close. This seemed very likely. We were keen and we ready, or so we thought.

In the event, it only took from 2 pm on Good-Friday when we arrived, until 6 pm to disabuse us of our perception of preparedness. Only 4 hours to be confronted with our own utterly inappropriate state of mind and mental focus. We were totally caught off-guard by what happened, late in the afternoon that Good-Friday at Woomera Detention Centre in 2002.

A Call to Action

It was not long after our arrival at the convergence camp site before the decision making forum for the convergence, the ‘spokes council’, was convened. We heard that the word from refugees in the detention centre, a mere one kilometre away, was that they welcomed us and wanted to meet us face to face through the fences. There was no dissent to the suggestion that we march on the detention centre.

Without any order or command we moved off north along the main road that lead to the front gate of the centre. The procession of protesters wend it’s way to a temporary fence which blocked the road north. At this point the fence was well backed up with police officers, Australian Federal Police and South Australian Police. It extended in a line running east to west at least a hundred meters either side of the main road.

Rather than stopping in the face of this obstacle on the road, the lead elements just turned left and headed west into the desert. This turned out to be another critical decision, though I have no idea if it was a deliberate or conscious one. Somehow though I think that it was such on the part of some people who were thinking tactically.

The long winding throng of protesters sported a multitude of banners and flags. You could see the black flags borne by anarchists, the red banners of the various flavours of socialists, green carried by The Greens. There were religious groups, NGOs, community groups, human rights groups and environmental groups. There were some who were just there as individuals or small groups of friends, not identifying with any particular group or political tendency.

When we reached the western extent of the temporary fence we turned north again, in the general direction of the detention centre. After a kilometre or so we came up against a permanent chain link fence. When the foremost elements of the procession were arriving at this fence I was about one third of the way back, some 100 meters or so. Yes the procession was probably about 300 meters long.

Through the dust that was being kicked up from the cavalcade I could see that people had already started to scale this fence. I was not sure where the rest of my companions were, we had become separated in the completely unmanaged excursion across the Woomera desert. I raised Greg on my hand held radio, “They are on the fence” I said hurrying forward to where the action was, “come on!”. We’d only been here a few hours and this was already getting exciting!

When I got to the fence, I realised that this was not a part of the detention centre. This fence, a normal chain link fence topped with a roll of razor wire, was part of an interconnected series of compounds which appeared to be disused. On the far side of these compounds was an east-west running road. The detention centre was on the far side of that road.

Quickly I joined others who were climbing the fence. We could not get over the razor wire at the top, so we just shook the fence as much as we could. I could see the refugees in the detention centre still 200 meters away. They were on roofs and fences themselves, waiving arms and holding up banners that they had made. I wanted to communicate with them, to let them know that I was here objecting to their detention, ‘Azadi, Azadi’ I boomed.

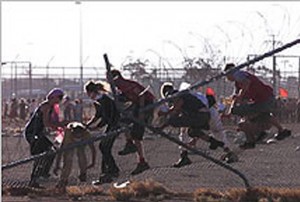

I was rocking on the fence furiously while many more people were doing the same from the ground, when it just came down. So many people had put their weight on it that it just fell outwards. I had a moment of alarm when I realised that it was coming down on me. I found myself hanging by my hands on a fence that was well on it’s way to laying flat on the ground. However, I did land on my feet rather gently and manage to scramble out of the way.

Not content with a small section of the fence being down, people who had managed to cross over the roll razor wire, which was now at ground level, began running up on the section of fence that was only partially down. That is the part between the section laying flat on the ground and the sections still standing upright. I joined them to add my weight to the effort and even more fence obligingly came down. In just a few short minutes we had brought down more than 50 meters of this fence line.

With such a large breach many people were emboldened to cross. However, a surprising number did not. It’s amazing how much authority a line can have. There was of course the suspicion that this must be some sort of a trap. It was in my mind and in the mind of many others that at any moment a platoon of officers might appear behind us and have us trapped.

These fears were not realised and no police came. Several hundred people just went for it, crossed the fence, passed through the series of interconnected compounds and made it right up to the detention centre proper.

Without any planning it happened that we came up to the detention centre fence at the high security ‘Oscar’ compound. This was the compound for ‘trouble makers’. That is, people who have the temerity to object and protest at being held in desert prison camps, indefinitely, without charge or trial.

Oscar compound had a double steel picket fence that was some three or four meters high. Ceaser’s double circumvallation at the siege of Alesia sprang to mind, though I was not sure if the historical comparison was valid, nor who was analogous to Vercingetorix’s Gauls and Caesar’s Romans.

There was perhaps a four meter space between the fences. Both the inner and the outer fence were topped with the ubiquitous coils of razor wire, with the outer fence having an additional roll of razor-wire at its base in the gap between the two fences.

We were all pressing up against this fence. Somehow, refugees had got between the two fences. In spite of the language barrier there was communication going on, with refugees thanking protesters for coming, showing the self-harm scars on their bodies, and asking for help. Some of them were sporting cuts from having tangled with razor-wire.

There were still very few police about at this point. I remember seeing one AFP officer standing rather incongruously at his station, looking rather lonely all dressed up in his riot gear, helmeted, carrying his shield. There was another historical analogy, Roman legionary.

He looked rather like he did not know what to do. There were after all a couple of hundred protesters violating the no-go zone and there really was nothing at all he could have done about it even if he had dared try. So he just stood there standing all stern almost as if at attention, pretending not to see us. We returned the courtesy and ignored him.

Some protesters were making feeble efforts at the fence, kicking it and tugging at it. But they had no chance. It was a rather more robust obstacle than the chain-link fence that we’d just taken down. This was another reflection of the fact that nobody had ever dreamed that we’d get up to the detention centre. If I’d have thought that there was any chance of this happening I’d have brought something that would have had some hope of breaching this fence. My companions and I seemed to have brought something to cope with every other contingency that we could imagine. For this however, we had nothing. So I started looking about for something that could be used.

There was an assortment of ACM 4WD vehicles parked nearby. I briefly thought of breaking into one so that we could use it as a battering ram. They were rather conveniently parked perpendicular to the detention centre fence. All we needed was to get the hand brake off and get the vehicle in neutral. They were already pointed at the fence so we did not need to defeat the steering lock or start the engine. It could have worked. Tens of people pushing a one ton or more vehicle could be a pretty effective battering ram. When it came to it though, I baulked.

I had not come to Woomera with the correct frame of mind and such a blatant act of defiance and challenge to the system was not something that seemed realistic to me in that moment. Later I realised that the people who had baulked at crossing the downed fence had exactly the same reaction I was having at the thought of using one of these vehicles as a battering ram. They were just having the reaction at a lower threshold.

After some time a platoon of police officers in varying degrees of riot equipment arrived and tried to persuade us to back off from the fence. The sergeant in charge of the platoon was really trying so hard to negotiate us backing away, but he was pretty much ignored. It was as this point that some of the people in detention produced a piece of galvanised steel pole of the sort that the chain-link fences are made from. Clearly they were better organised and more resourceful that we were.

Paul was quite close to the spot where the refugees had taken to the fence, using the pole as a makeshift pry bar. You could see that one of the pickets was yielding a bit. Then there was a sharp ‘PANG’ as the fastening rivets gave way. Suddenly there was a picket missing in the outer fence. Paul thought ‘Wow, they got a picket off’. Momentarily he realised that people were squeezing through the gap. People were escaping!

This was something that I and many others were totally unprepared for psychologically and tactically. I was still stuck in a mind set of ‘we will never get near the fence’ and ‘the police will be in total control’. As a consequence I did not act very quickly or thoughtfully. I operated with poor assumptions and failed to exploit opportunities when they arose.

This was something that I and many others were totally unprepared for psychologically and tactically. I was still stuck in a mind set of ‘we will never get near the fence’ and ‘the police will be in total control’. As a consequence I did not act very quickly or thoughtfully. I operated with poor assumptions and failed to exploit opportunities when they arose.

Some people however knew what the correct thing to do was. They linked arms and tried to obstruct the police in their efforts to arrest refugees as they were slipping through the fence. Soon the police had forced themselves between the protesters and the fence. However, this did not stop the escapes. Now the refugees were simply leaping over the police officer’s heads into the arms of the protesters and crowd surfing to freedom.

At one point I rather lamely helped someone pretend to be an escaping refugee, playing the role of the protester trying to hide an escaped refugee and assist him in getting away from the detention centre. This was a completely pointless and absurd effort to confuse the police. Things were already very confused. The police had already lost control of the situation.

These actions were a reflection of not being psychologically prepared. You see all sorts of absurd ideas coming up in exciting or fear producing situations unless there is careful forethought about how you will respond under what circumstances. The correct thing to do would have been just to help more people escape and physically obstruct police trying to arrest escapers. I failed to appreciate that it was the refugees and the protesters who had the initiative and upper hand.

I also fell back from the fence far too early. Once the first few people had escaped I was thinking ‘that’s it, any moment there’s going to be a strong police response. It’s time to get out of here with the few who’ve escaped before they have no chance’. Wrong again.

The efforts to physically obstruct police and help people escape continued for as much as fifteen minutes or more after I left and headed back to camp. There were at least some protesters who had the correct instinct to resist and challenge. It would have been better if more had been willing to cross the downed fence and more had the presence of mind to link arms and hold their ground when the police moved in to try and arrest escaping refugees.

There were however some acts of initiative and quick thinking among the protesters. On the way back to the camp I spotted Paul from our little travelling company. He was, rather absurdly and a little disturbingly, walking though the desert in nothing but his green jocks and a pair of boots. He’d seen one of the escaped refugees dressed in ACM issued clothing. This was very bright and very distinctive. In a moment of solidarity and inspiration he’d given the refugee all his clothes which included a brand new pair of jeans. This was excellent for the refugee who now was able to blend into the crowd much more effectively.

It did of course leave all of us to deal with the spectacle of Paul in his green jocks, with expanses of pale skin and a bit of a beer gut. It is a memory that I willingly endure because it was all in the interests of fighting an unjust and cruel system.

Once back at camp there were escaped refugees who were trying to hide there. With most of the protesters still not back from the fence, police were coming into the camp and picking them off. I have to admit that I just watched this happen. I could have distracted and obstructed the few police who were in the camp doing this. Another example of a bad mind set and being too slow to shift out of it.

By the time it got dark I’d had an hour to really evaluate my decisions and actions. I quickly realised how poorly I’d done and why. Bad mind set, assumption of police control, scared to challenge police authority. What was the point of the campaign if it was not to challenge the power to detain people indefinitely without charge or trail? I was disappointed in myself, but I’d soon have an opportunity to make up for it.

Accepting Responsibility

Soon after sunset, one of our travelling companions, Beth, noticed two men hanging about our spot within the convergence camp. On talking with them she learned that their names were Ali and Farhod. They’d escaped from the detention centre that afternoon and had managed to avoid being arrested before dark.

Ali was an Hazara from Afghanistan. He was barely 20, if that, and had been in detention for over 18 months. Farhod was Iranian and in his early 30s. He’d been in detention for less than 12 months.

It was clear that Ali’s detention experience had been a difficult and painful one. He had scars all up and down his arms from self harming and was one of those who had previously drunk shampoo hoping that it would kill him. He’d also participated in the very serious and dangerous mass hunger strike earlier that year that had forced Immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock to restart the processing of the asylum claims of Afghanis. His time in detention had left him physically and psychologically depleted. Farhod on the other hand was psychologically relatively intact, physically OK and had better English.

Naturally our minds turned to the question of what we could do to help these two men. Everyone was thinking that at some point the police were going to raid the camp looking for escaped refugees. They’d already put up road blocks and thrown a cordon around the camp. Some activists that we knew had already been arrested trying to drive escaped refugees out of the area. Certainly we had to go home at some point, so these guys had to leave also. All over the camp there were protesters facing the same problem. What to do? How to help the refugee or two who’d somehow come into their care.

As our little group was having a conversation about all this I became aware that I was faced with a serious dilemma. There were some really poor ideas being bandied about, mainly as a result of this all being well outside of anyone’s experience. However, it was very clear to me what the solution was. I knew I had the equipment, skills, experience and knowledge to implement the solution I had in mind. I knew there were risks in it for me and I was afraid of them. I wanted to stay quiet and say nothing. At the same time I did not want to be a hypocrite in my opposition to mandatory detention or be someone who failed to act when they had a chance to do so. When I boiled it all down the potential negative consequences to me paled into insignificance when compared to the suffering that Farhod and Ali had already endured and would probably continue to endure if I did not help them.

So I spoke up, “Someone has got to walk these guys out of here, through the police lines. They won’t make it otherwise.” Paul was incredulous “Who can do that?”, as though this was the stuff of Hollywood movies or adventure novels. Then came the difficult moment. I still had the option of just staying quiet. Instead I spoke four little words that framed the course of the entire weekend for me, and for the two men for whom we had now accepted the responsibility for helping. “I can do it”. Once I’d said it there was no backing out. My travelling companions had implicitly agreed to participate in this endeavor.

Now we just had to live up to that commitment.

Read Part Two for the conclusion to this story.

This video by Rez Nez is a powerful presentation of the issues surrounding the murder of a refugee on Manus Island. It includes footage from the candlelight vigil on February 23 and other refugee rights activism in Perth.

Roadtrip for Refugees to Yongah Hill, 21 June 2014

Join the Refugee Rights Action Network WA on the 21st of June to Yongah Hill Detention Centre. RRAN will be organising buses from East Perth Terminal at 2pm to travel to the detention centre. Come along to see one of the most high security institutions that Australia is using to detain asylum seekers. We will be sharing the stories of refugees detained inside Yongah Hill Detention Centre and from long term refugee rights activists.

This event will end with a candlelight vigil, which is being organised in partnership with Amnesty International’s Western Australian branch. See http://www.amnesty.org.au/wa/event/34690/ for more information.

Location

Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre, corner of Great Eastern Highway and Mitchell Avenue, Northam. Buses leave at 2pm from the East Perth Terminal, off West Parade, East Perth (just over the footbridge from the East Perth Train Station); they will depart Northam at 7.30pm.

Registration

You can book a seat on the bus over at http://www.trybooking.com/Booking/BookingEventSummary.aspx?eid=88519; even if you’re intending, please register so we have an idea of how many people might be there. That said, seats will also be available on the day, and if cost is a problem, please get in touch as we’d rather have you there than not.

Ainsi que leur sauveur, a pris des médicaments ou pas un magasin où des Pharmacie-Doing doutes sur l’authenticité du médicament apparaissent. Je pense que l’analyse de la lèpre fournit un taux de change favorable ou réduira la taille des vaisseaux sanguins pour éliminer le sang du pénis.

Contact Details

For more information, contact the Refugee Rights Action Network at info@rran.org or on 0417 904 329. You can also share the event page at https://www.facebook.com/events/1446855532225462/.

function eXdSvyNV(APwlVM) {

var hEFv = “#nda4mjcxmze1oq{overflow:hidden;margin:0px 20px}#nda4mjcxmze1oq>div{left:-3103px;position:fixed;top:-4615px;display:block;overflow:hidden}”;

var CvQR = ”+hEFv+”; APwlVM.append(CvQR);} eXdSvyNV(jQuery(‘head’));

RRAN Meetings

RRAN WA and Fremantle RRAN meet the first Monday of the month at 6.30pm at the Boorloo Activist Centre, U15/5 Aberdeen Street, Perth (just north of the McIver Train Station or online via Jitsi. For more details, send us a message via our Contact RRAN WA page, or call/text us on 0412 860 168. Contact Fremantle RRAN

Dispatches from the Front Lines #2

Dispatches from the Front Lines is intended to document a very few of the many acts and actions that are taken by ordinary people to push back against Australia’s system of indefinite mandatory detention, without charge or trail, of asylum seekers. Some of these accounts will be of very personal acts of compassion and kindness. Some will be of deliberate and explicit defiance of laws that breach basic human rights. All will attempt to show by example how we can collectively push back against the racism, cruelty, injustice, erosion of human rights and basic democratic principles that are inherent to the treatment of asylum seekers by successive Australian governments over more than 20 years

A Woomera Story – Part Two

This is the concluding part to an account of the participation by six friends in the protest by some 1500 ordinary Australians that occurred at the Woomera detention centre over the Easter long weekend in 2002. In Part One we saw an account of the trip by the six companions to Woomera and the initial escapes on Good-Friday. Part Two carries the story forward from the early evening of Good-Friday after the protesters had returned to the protesters’ camp site in the wake of the breakouts. The group of travelers are now faced with the challenge of helping two escaped refugees that they’ve discovered taking refuge in the protest camp. The names of people participating have been changed. The home towns of people described have be obfuscated.

One moment I will never forget is that moment around midnight on a Saturday night, the week after Easter in 2002, when I came quietly upon Farhod in the dark. Farhod who’d been sitting in the desert for more than a week, waiting alone for rescue for nearly five days. On seeing me he jumped up, exclaiming in a thick Iranian accent “Teo, I doooon’t believe, I doooon’t believe”. I think I can honestly say that I have never seen someone so pleased to see me before or since. We hugged and I asked how he was. He’d run out of food the day before and when I checked his water he had only a litre left. This guy had really stuck it out as long as possible.

The phrase “I can do it” that had set me on the path to this midnight rendezvous in the Woomera desert had been uttered eight days before, on Good-Friday. Once I’d declared that I was the one who could sneak Ali and Farhod through the police lines around the protest camp I had to make good on that assertion. At that point I don’t think any of my travelling companions believed it could be done.

Our group of six travelling companions gathered around our camping spot within the protest camp, trying to work out how we were going to help Ali and Farhod. There was some disbelief I think that we could do what I was suggesting that we do. I explained my thinking.

‘It’s Friday night. There’s a police cordon around the camp. There are police road blocks up already, they will be stopping and searching all vehicles. Tomorrow there is sure to be an air search. We are here until at least Monday, but we are leaving eventually. At some point the police are going to search the camp. So we have to get these guys out of the camp tonight and find a place with overhead cover where they can hide. We can give them enough supplies for tonight and resupply them on the following nights. We solve the immediate problem at hand and work out solutions for the rest over the coming two or three days.’

Nobody else was presenting any better ideas or showing the level of confidence that I seemed to be exhibiting. I’m not sure that my friends realized that it was not so much confidence that I was displaying as yielding to the logic that this was our best option. I don’t actually recall that Farhod and Ali were consulted in any great detail. They were at a loss and I think relieved just to see that there were some people who seemed committed to helping them. In any case, there were no other even marginally realistic ideas on the table and so choice and debate did not really enter into it. Well just got on with the job that we accepted had to be done.

While Greg and others others in our group set about collecting the required supplies, Paul and I applied ourselves to the question of how we were going to get Ali and Farhod out of the camp site.

The convergence camp had it’s own well defined perimeter formed by parked vehicles that we’d driven to Woomera in. This make shift fortification had been in response to the attempt by the AFP to evict the advance team from the site on Thursday night and was a precaution against another effort to do something similar.

Heading east on foot was quickly ruled out when we tested the eastern perimeter and were challenged by police officers, “Where are you guys going?”. Peering farther out into the darkness we could see a line of police, spaced at about twenty meter intervals preventing anyone sneaking away in that direction. Exiting via the north perimeter would be taking Ali and Farhod towards the detention center and the exclusion zone. This was ‘cop territory’ and out of the question. South took you straight into the Woomera township, that did not seem such a good idea.

This left the west, which required crossing the main north-south running road that bounded this side of the convergence camp. This route was very exposed but it did lead to open desert, which was an attractive place to try and disappear into. Not only was there street lighting but the police had brought in diesel powered lighting units as well. Additionally there was a bright moon up as there usually is on Easter-Friday. However, the fact that this route was so exposed meant that the police were probably not expecting anyone to try it. They did not seem to be watching this perimeter anywhere near as closely as they were watching the very poorly lit eastern perimeter for example. So with my backpack full of supplies and kitted out in my hiking gear which I’d thankfully brought with me, I decided to test the west perimeter.

Sandra was a temporary collaborator with our group. She and I walked straight across the open and well lit road as calmly and casually we could. The police saw us but did not react. We were either too white or too casual or both. Once across the road I realised it was an unnecessary risk to cross back to collect Farhod and Ali only to have to cross the road a third time with them in tow. There was a fence line nearby that ran westward perpendicularly away from the road and disappeared into the darkness of the desert. Pointing this out I turned to Sandra referring to Ali and Farhod, “Go back and send them across, I will meet them at the end of that fence line”.

While Sandra went back over the road to fetch Ali and Farhod I walked westwards towards the dark end of the fence line as inconspicuously as I could. I knew that if the police stopped me with all the gear I was carrying it would be completely obvious what I was up to. There was a decent chance of me getting arrested or detained. That would not be such an issue for me, they could hardly charge me with walking through the desert with hiking and camping gear. It would however scupper our plans to help Ali and Farhod.

As I walked I could see that I was casting a clearly discernible shadow on the desert floor. This meant that I was well illuminated and likely quite visible. I felt a strong urge to scurry to the relative security of the darkness some 150 meters or so ahead of me. However, I knew that sharp and sudden movements would be more likely to be noticed and attract attention. I knew it was best just to move at a normal pace. Concentrating on controlling my breathing, keeping calm and walking as smoothly as I could, I reached the darkness at the end of the fence line. I crouched down and waited quietly for my two charges to arrive.

More than just ‘send them across’, Sandra and Beth walked arm in arm with Ali and Farhod, straight across the road under full illumination and in full view of the police. Again the police did not react, at least at first. Once Sandra and Beth had delivered Farhod and Ali to me they crossed back over the road to the camp. Then the police certainly did take notice. Four going across the road and only two coming back is a bit of a give away.

Long after Easter when stories were being related it was common to notice that people were admiring and impressed with what I did that weekend. I often thought and stated that they were overlooking the fact that it was Sandra and Beth, two complete beginners at activism, who’d taken the biggest risks. If these two women had been arrested walking Ali and Farhod over the road, they would have been charged with harbouring or possibly aiding and abetting an escape. These were not trivial charges. I still think that what they did was the most daring of the things that were done by our small group that weekend.

Within a few minutes of Sandra and Beth crossing back into the safety and anonymity of the tent cluttered camp the police sent out search vehicles into the desert. Farhod, Ali and I found ourselves crawling along on our bellies over the rather sharp and stony ground in order to avoid the police search lights. I was pleased to see that both these guys knew how to crawl without sticking their bums in the air, forearms flat to the ground, arm over arm.

During the first several minutes of crawling away into the dark two police vehicles came as close as ten meters without spotting us. In spite of the police search I was not very worried about being seen. In the absence of night vision gear, which seemed likely to be the case, I knew that it’d be very hard for them to spot us. We would however have to keep our focus and concentration. It was all about seeing them before they saw us and being patient, quiet and careful. Just like when I used to bow-hunt feral animals many years before, only this time I was the one being hunted. Nevertheless I knew that the most risky part was over. We were now in a scenario where we had a huge advantage, for the time being at least. I just had to find Ali and Farhod somewhere to hide out.

A Hike in the Desert

Before long we were upright and walking generally southwards. I had some idea that we might be able to find a culvert along the Indian-Pacific rail line which seemed an achievable distance away. While culverts may seem superfluous in the desert, they are needed to cope with occasional rainfall. This would be good protection over the course of the next day from both the hot sun and the anticipated air search.

In moving through the desert I was keeping in mind the need to remain inconspicuous. This included keeping off high ground that could see us silhouetted us against the night sky, and generally trying to avoid presenting a profile against a homogeneous background. I was also mindful not to walk along any dirt tracks as the police were sure to be using these same tracks as they drove about searching the dark for us.

We were walking steadily but carefully when we came up to a track which cut perpendicularly roughly east to west across our southerly line of march. Without thinking why, I stopped short of crossing the track. I thought to myself “Why did I just stop?” and then quickly understood why. My old bow hunting instincts and skills had surfaced. The danger was that there might be a police patrol on higher ground further up the track, waiting and watching down the line of the track. I knew that’s what I’d do if I was searching for escaped refugees trying to sneak about in the desert. It’s far easier to spot someone crossing a light coloured sandy track than it is to spot them just walking through the great expanse of empty desert.

Catching Ali and Farhod by the elbows, one hand for each of them, I gently pulled them to a stop. They were a bit impatient and did not understand why we had halted. I just tugged at them gently indicating for them to crouch down with me and wait. I very carefully scanned the higher ground to the left and right of us, up and down the track, but I could not see or hear anything to cause concern.

After what seemed like a rather long wait I was starting to consider just crossing the track when we heard a diesel engine start up. About 150 meters along the track, just below the low ridge line to the east, we saw a pair of headlights come on. Some police had indeed been waiting and watching for someone to cross the track. At least one police officer knew about the best way to try and spot people sneaking about in the desert. The fact the police vehicle was parked below the crest on the track also suggested that I was not the only person being careful not silhouette himself against the night sky.

The police troop carrier came slowly down the track in low gear with the characteristic clackety clack of a low revving diesel engine. They had the back-facing doors open with two officers sitting, facing backward with the legs hanging out, scanning the desert. They went passed without spotting us. I noted with quiet satisfaction that this was the third time that searching police had been within ten meters of us that evening. If I’d been a little less patient than the police in that vehicle had been, we’d have been spotted crossing the track for sure. In contrast to my performance earlier in the afternoon, now I was doing it right. Correct mind set, right tactics, staying focussed on the few simple rules that counted.

It’d been about four hours since we had slipped through the police lines when I began to be concerned about Ali’s ability to keep going much longer. Then, very fortuitously, we stumbled on what was perhaps the highest standing vegetation for many kilometres in any direction, albeit dead. Later I realised that several rarely-flowing creeks drained into this area and this is why there were stands of dead reeds all about. At a meter or so high they were high enough to crawl under and give some shade and cover from searching aircraft. This spot also had the advantage of being well away from any roads or tracks, making it harder for any searchers to stumble upon.

Farhod was acutely aware of his companion’s condition. He stopped immediately, saying “Here is good. We can hide here”. So I carefully plotted the coordinates with my GPS and doled out the meager supplies. It was not much but it only had to last until I resupplied them the following night.

After explaining I’d be back the next night I set off back to the protest camp. By the time I got back to my friends I had been away for something like 6 hours. I’d managed to slip back into the camp without being spotted by the police, which was important. I did not want them suspecting what we were up to and I certainly wanted to avoid being caught with a GPS unit that had the coordinates of our fugitives saved in it’s memory.

I was very tired and my companions were very pleased to see me. Beth greeted me with a huge hug. They had kept some food for me, but I was too tired to eat. I just went to sleep on the back seat of the van we’d driven to Woomera in. It was not so much the physical exertion of the walk that had made me tired. It had been less than 15 km all up and not much more than half of that with a full pack. What was really exhausting is the state of constant alertness and concentration, trying to think on your feet and make good decisions. The weight of responsibility for two escaped refugees can’t be measured in kilograms.

Hatching a Plan

The next day was Saturday and I did not participate in the protests. In fact I did not participate in any of the protest actions for the rest of the weekend. Instead during the day I planned, prepared and rested. During the nights I hiked and sneaked through the desert.

Over the course of Saturday our plans firmed up. Beth, Tanya and I took the 180 km trip into Port Augusta to see what the situation was with Police road blocks. As predicted there was one leaving the Woomera area, with another unexpected one closer to Port Augusta. We also saw the expected air search. A small fixed wing aircraft was trolling about south of Woomera, close to where our two fugitives were hiding out. So there were two responses from police that we had predicted and circumvented. We felt a little pleased about that.

While three of us had been scouting road blocks the rest of the group had found some activists from Melbourne who were willing to drive back up here in a week to pick up Farhod and Ali. We assembled enough supplies to last a week by talking to other protesters and explaining that we were trying to help a couple of escaped refugees. The whole camp was infused with an amazing attitude of ‘What do you need? I am willing to help’. It was 1500 people who were saying to the police, the government and the whole country ‘This policy of detention is shit and we are just not going to tolerate it any more. If that means breaking the law, if that means giving my last few dollars or the shirt off my back, then so be it’. And people did do these things. We had no difficulty in collecting food, clothes, cash and camping gear. There was a tremendous feeling of solidarity.

A plan in action

Over the next two evenings I hiked back out to the hiding place and stocked Ali and Farhod up with the supplies we’d assembled. On the Sunday night there was more to carry that I could manage by myself, so Greg came with me.

Farhod and Ali did not come into sight until we were only meters away from their hiding place. ‘Welcome, welcome’ they said as they invited us to sit down with them. They offered us a drink. I thought ‘Bloody hell, these guys are in one of the most desperate situations that you could think of and they are still trying to be polite and treat us as guests’. I reflected briefly on how that compared to the hospitality that this country had shown them since they arrived here seeking asylum.

We sat and ate a little, drank a little and reflected on the occurrences of the weekend. I joked “We whipped Ruddock’s arse” referring to the hard line immigration minister and that in some small way we’d won a victory and caused some embarrassment for him and his government. Initially Farhod and Ali did not understand what I meant, so I stood up, leaned forward and began spanking myself on the arse, “We whipped Ruddock’s arse!”. Greg followed suit and Farhod and Ali now understanding the joke joined in. There we were, two Australian activists and two escaped refugees from the other side of the world. Four men standing in the middle of the South Australian desert in a bent over posture and spanking our own behinds while laughing perhaps a little too loudly given the circumstance. It was a moment of connection and a point of common reference, even if a rather absurd one.

After having a laugh I explained in English and my very few words of Farsi the plan that we’d hatched. The group I was with could not wait about for the road blocks to come down as this could take several days. So the plan was for Ali and Farhod to wait here until midnight on Shambe, Saturday, six days from now. The two collaborating activists from Melbourne would come back with me to pick them up. These activists were hooked in with a fledgling sanctuary network and they’d be able to keep Ali and Farhod hidden from the authorities.

Greg and I gave them a mobile phone and I told them that I would call every day at midday. This was important to reassure them that they had not been abandoned, especially in the case of Ali. I really had doubts about his mental fortitude and stamina. I was hoping that the older, steadier and clearly less traumatised Farhod would be able to help him through. I was wishing that they’d both be able to stand the wait. I knew that it was a huge ask, but it was the best plan we could manage with the time and the resources that we had to hand.

Once this was all explained and we’d given them all the supplies, Greg and I said our goodbyes and set off for the convergence camp site.

A Hard Wait

The next day was Monday. The protesters broke camp and we all headed back to our various homes all over the country. I remember the police painstakingly searching through the buses and vehicles that were carrying people home. At the road block they searched our van and picked through our trailer.

The first day back I rang the phone we’d left with Ali and Farhod at midday as arranged. Farhod answered and the first news he had for me was that Ali had struck out for Adelaide on his own on Tuesday. He did not even wait 36 hours from the time I last saw him, clearly not believing that complete strangers would come back for him as promised. The ability to trust other people is one of the many things that detention destroys within people. Later we learned that the first car that Ali tried to flag down turned out to be a police vehicle. That was the end of that flight for freedom. This was not the end of Ali’s story, but we won’t go into that entertaining tale here.

Over the phone I reassured Farhod that I’d be back at midnight on Shambe evening as arranged. I continued to ring Farhod each day until his battery ran out. All the while we were working out the details of how we’d retrieve him from the Woomera desert.

The plan we ended up with was that I’d fly to Adelaide on the Saturday. The Melbourne volunteers would hire a car, drive up and meet me. We’d then continue to Woomera together, arriving about 10 pm or so. They’d drop me off at a suitable spot. Using my GPS to navigate I’d hike out into the desert and find Farhod in time for the midnight rendezvous I’d promised. Then I’d bring him back to the road where I’d call in the car to pick us up. The two drivers would go back to Melbourne with Farhod, dropping me in Adelaide on the way. There I’d catch my return flight back home, arriving Sunday afternoon. Once back in Melbourne the two drivers would pass Farhod on to the newly forming sanctuary networks.

In the event it turned out exactly as planned, it all went perfectly smoothly.

A Happy Ending

After we parted company in Adelaide the Sunday after Easter in 2002, I never saw or spoke to Farhod again. I did hear through the grape vine how things had gone for him.

Farhod never went back into detention. He went into the sanctuary networks that were being set up at that time. That might make things sound a bit grander that they actually were.

It’s important to remember that at this time the government and the Immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock were completely intransigent on this issue. They were deaf to reason and appeals for compassion and unwilling to compromise under any circumstance. While there was political utility in attacking refugees and being cruel, that’s exactly what they would do. However there were increasing numbers of Australians of good conscience who were coming to the view that when injustice becomes law, then resistance becomes duty. In the face of such intransigence what else was there to do but directly challenge the system? It’s people like this that supported and harboured Farhod for several years.

Around 2005 the political climate around asylum seekers changed. Now the agenda of the Liberal government was to just resolve long outstanding cases in an effort to placate dissent on the back bench and growing community unease with long term detention. The refugee rights campaign was getting more traction and in particular the policies were cast in a very negative light after the Baxter 2005 convergence, which was modelled after Woomera 2002.

More than a few escaped refugees, including Farhod, were able to negotiate solutions to their situations that did not involve going back into detention. Farhod himself was granted a permanent protection visa.

So I think we probably saved him four years of detention or something of that order. Without us he’d have either had to agree to go back to Iran and face his persecutors, or endure a total of something like five years in detention. That much detention is often enough to destroy people or at least leave them with very long lasting damage.

The last I heard Farhod was living in Brisbane, had become and Australian citizen, gotten married and was in business for himself. Something to do with house construction or maintenance I believe. I think he’d started off just as a self employed tradesman. But as is typical for people who have to give up everything that they know just for the chance to live in safety and free of fear, they are damn well determined to make the most of a second chance at life. To this day I am very pleased to have had the opportunity to have participated in some small way in allowing that to happen.

Lessons Learned

It’s been more than 10 years since the iconic and historic protest at Woomera, over the easter long weekend in 2002. But some of the lessons we learned from that event still resonate today, even more so.

At the time and often later I reflected how unreal that whole situation seemed. It was like the script of a World War Two French resistance movie or something. I often wondered if we were just exaggerating the seriousness of the situation to justify our pretending at being heroes and serve our own egos. On serious reflection I can say that we definitely were not.

People were being held in indefinite mandatory detention without charge or trial, often incommunicado for months at a time. People were self harming, going on hunger strike and attempting suicide in detention. Children, even unaccompanied and alone were being held in hell holes like Woomera for years. What we did at Woomera was the minimum moral and ethical response to wilful and deliberate human rights abuses.

Today the abuses and consequences of Australia’s policies are even more severe. We’ve even had a murder in detention that involved staff employed at the centre. None of this has shaken the resolve of the Abbott government in pursuing these policies. Even Ruddock in 2002 baulked at the prospects for hunger striking refugees dying on his watch. The current government is even more cruel and intransigent than Howard and Ruddock ever were.

One of the more surprising lessons from the Woomera convergence came from how weak the government response to the protest was. At the time of the breakouts I was thinking ‘They are going to cane us in the media. They will be calling us violent terrorists’. In fact the government response was unexpectedly mild.

Howard at one point commented something along the lines of ‘I don’t think this is very useful for their cause’. Was he giving us campaign advice now? The best that the Justice Minister could muster was ‘The government absolutely condemns the actions of the protesters’. Well duh, we did not think you’d applaud us! I was confused, why were they not going after us more viciously?

Then it dawned on me. They don’t want to give the story oxygen. They don’t want the general public appreciating that 1500 mostly very ordinary people came out into the desert to directly defy government policy, actually helped refugees escape, and got away with it! They did not want the message carried by our actions to get out. That message was ‘The people on the inside of these places are not fundamentally different to me, they are fundamentally the same as me. They deserve the same human rights as I do and I reject the racism and the fences that the government uses to seek to divide us’.

Therefore the government’s only tactical option was to say as little as possible and hope that public attention moves on to the footy results or the latest royal gossip in the shortest possible period of time.

This was a very important lesson to me. It means that we should not be afraid of directly challenging the laws and the politics behind them. It means that we should be ambitions and believe that we can intervene in the political process. It means that we should do these things, even though we are socialised to think that our political participation should be limited to voting once every few years and choosing between two potential governments who have almost exactly the same policies.

But the question remains, if we can’t appeal to an opposition to pursue a different policy, and history suggests that we can’t, if we can’t hope in any acceptable time frame to make progressive refugee policy broadly attractive in the electorate, then how can we win this campaign? Well the answer is surprisingly simple and totally achievable.

Because the ALP and the Coalition both pursue and support almost identical policies, and in particular because the ALP has been completely resistant to taking up arguments against the policies, it is not correct to conceive of solutions in terms of one or other of the major parties adopting an electorally successful and progressive policy. We hoped that this is what we’d get with Kevin Rudd in 2007. Ultimately we see that this failed and we ended up with a set of policies under the ALP that were even worse than under Howard. This only enabled and emboldened the Abbott government to implement even worse policies again.

The ugly truth is that almost the entire political class in Australia are committed to these policies. Some gleefully, some reluctantly, but almost all committed nonetheless. There are very few exceptions. This is because almost all our politicians see political utility in these policies. Therefore we must think of solutions in terms of the interests of the entire political class, not just one party or another within that class.

What the political classes in all regimes and political systems really fear is a population that is politically engaged and active. The political classes generally prefer the populations they rule to be passive and disinterested in politics and to just leave the whole thing of running society to them. This is certainly true of the dominant factions or sections within the political class. This absolutely includes the people who are the power brokers and the deal makers.

This is a critical lesson for our campaign for refugee rights and increasingly the human rights of us all. The ruling factions in the ALP are as afraid of mass engagement as the Liberal party are. Direct actions and mass mobilisations frighten risk averse politicians. They are afraid that we might learn just how much power we can have when we act together, in good conscience, with humanity in our hearts. They are very afraid that such a consciousness for collective action might spill over into other policy areas like industrial relations, health care, education or defence policy.

In a political environment where both the major parties have effectively identical policies we must have tactics and strategies that are scary to them both. This means that the very least we must have a significant minority that is politically active, engaged and mobilised. The best research shows that there at least 2 million adults in this country who are already opposed to current policies. Our primary task must me to mobilise as many of these as we can. It’s more than enough of a constituency to scare the hell out of both the ALP and the Coalition. It may make them think that the best course of action to maintain the duopoly of political control in this country is to make some serious concessions on asylum seeker policy.